Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Researchers Seek Clues to Celiac Disease

This story, written by Sharon Tregaskis, is excerpted from Pitt Med magazine's winter 2017/18 issue.

When you have celiac disease, your immune system goes berserk in the presence of gluten, the protein that gives bread its stretch. The resulting blitzkrieg turns the villi — the microscopic, finger-like protrusions within the small intestine that absorb nutrients and fluids — into the targets of a search-and-destroy mission.

You can’t feel anything as the villi flatten and atrophy, but the resulting dysfunction — gas, bloating, diarrhea, constipation — takes its toll. And that’s just for starters. As the damage spreads, the symptoms intensify: malnutrition, behavioral and mental health problems, joint and muscle issues, reproductive dysfunction, even increased risk for some forms of cancer.

There is no cure. But for many people with celiac, in the absence of gluten the attacks subside, and eventually the villi can heal — like skin slowly repairing itself after a burn. Yet probably less than 20 percent of people with celiac get an accurate diagnosis.

As for eliminating gluten, that’s no easy task with this darling of the food-processing industry. Some things are obvious — bread products and anything that contains wheat or a half-dozen related grains. But gluten also lurks in the shadows — in condiments, spice mixes, thickeners, even the coating that gives French fries their crunch. When you have celiac, eating away from home turns into an exercise in Russian roulette, and reading ingredient lists becomes a matter of survival.

Approximately one in 130 people worldwide will develop celiac over the course of their lifetimes. “That sounds like long odds,” says the University of Pittsburgh’s Vira I. Heinz Professor of Pediatrics Terence Dermody, “but it’s not.” These days, everyone knows someone who has it.

The puzzling thing, says Dermody, who is chair of pediatrics, is the disparity between the prevalence of the gene variants that confer the risk of developing celiac and the relative rarity of the disease itself.

Between 40 and 50 percent of us have the gene variants for celiac. They’re ticking time bombs. Even as we happily make like Eric Carle’s very hungry caterpillar — swilling beer and blissfully, ignorantly noshing our way through the Super Bowl buffet — the switch is poised to flip, ready to turn a benign foodstuff into kryptonite.

“So what gives?” says Dermody. “Why isn’t celiac more common?”

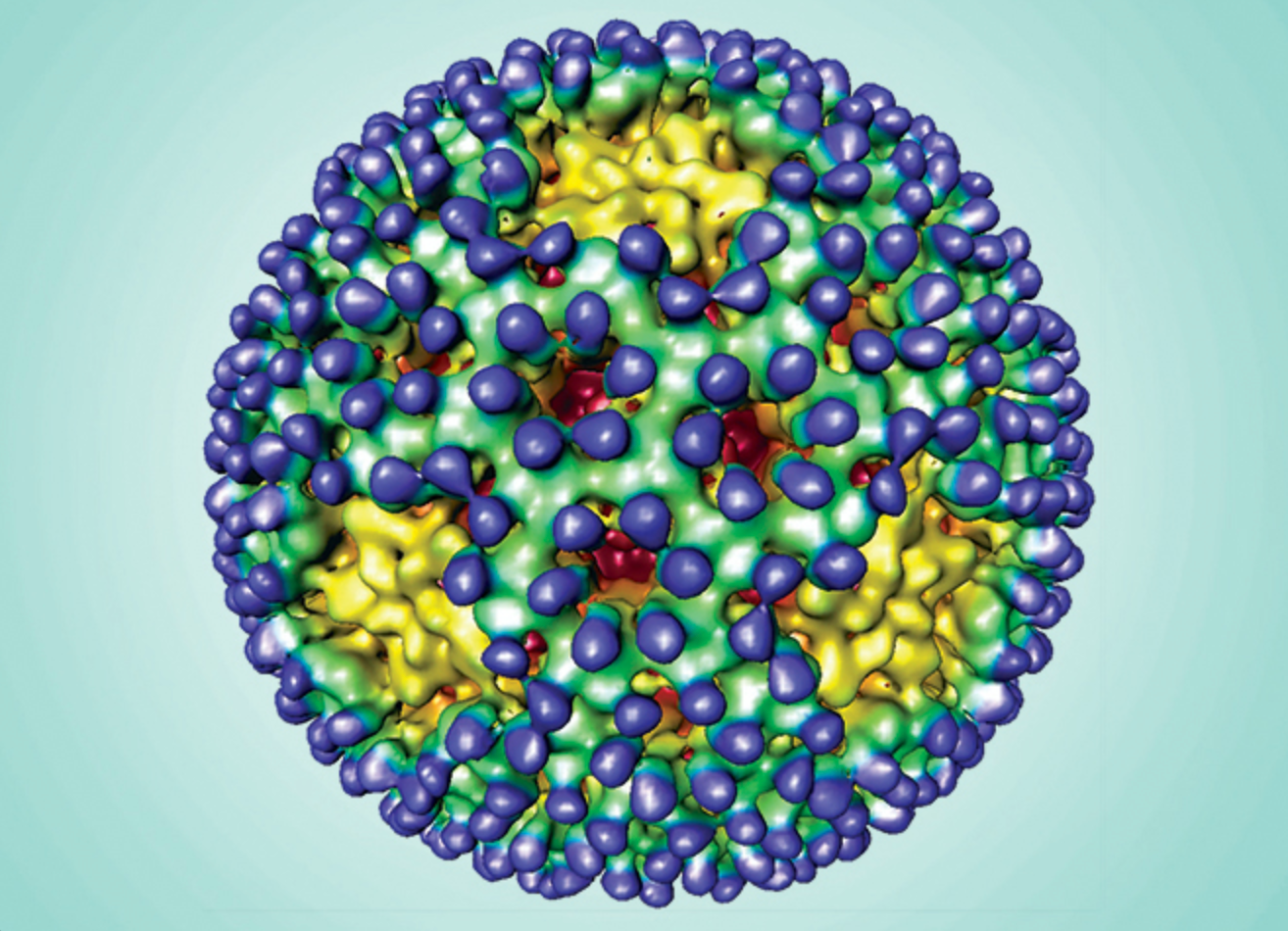

In April 2017, Science published results of a series of experiments by Dermody and colleagues at the University of Chicago that begin to offer an answer: a combination of wrong-time-wrong-place factors that converge around reovirus, a bug so innocuous that most of us have had it and never even noticed. Even its name — an acronym conferred in 1959 by live-oral polio vaccine developer Albert Sabin — evokes its presumptively benign role in human health. Isolated from the respiratory (r) and enteric (e) tracts, or intestines, of human patients, it was an orphan (o) to which scientists at the time couldn’t tie a single human disease.

Board certified in infectious disease, Dermody has spent more than three decades studying reoviruses; he is becoming one of the world’s leading experts in the field. Reovirus is the fruit fly of virology — ubiquitous, inexpensive to maintain in a laboratory setting, and possessed of a relatively simple genome. That combination makes this virus family the perfect model for basic virology. In the 60 years since reoviruses were first isolated, scientists have built an extensive body of knowledge describing and manipulating their RNA, developing models and digging into just how viruses leverage host biology to perpetuate their own genomes. And reoviruses are pretty much harmless.

“I can look in the eyes of the mothers of my students and postdocs and tell them the virus isn’t going to hurt them, and they’ve already been infected,” says Dermody. He has supervised more than 90 aspiring physicians and scientists in his laboratories at Harvard, Vanderbilt and, since January 2016, the University of Pittsburgh.

Although human exposure to reovirus doesn’t cause any symptoms of disease or leave a trail of damage in its wake, the virus can’t just skate past the immune system. At some point, probably early in life, reovirus makes its way through our guts, and our adaptive immune system generates antibodies that stay with us for life. That’s how we know most of us have been infected.