In 1991, Carl Ware is climbing ever higher on the corporate ladder at the Coca-Cola Company. The iconic corporation has just named him deputy group president of northeast Europe and Africa. As one of his first actions in the prestigious position, Ware schedules an in-person meeting at his London office with all the managers throughout Africa.

The gathering of executives is eye-opening.

“It was the epitome of the colonial system in Africa. All the managers — whether they were French, Afrikaners, Rhodesians, German or English — were white,” recalls Ware. “And if that wasn’t enough, all the expats from the U.S. in the London office in finance, marketing, legal and all those jobs were white males.”

Ware asks the men to raise their hands if they believe in the future of Africa. Hands raise. He then asks if they believe they could, within the next five years, find a Black African who could do their job. No hands raise.

He remembers their explanations: “They said they’d been looking and either couldn’t find one or, if they had, they’d been poached by other companies.”

Ware pushes back: “Don’t tell me that can’t be done,” he tells them, “Because it can. And that’s what we’re going to do.”

Ware is used to overcoming and getting things done. Setting high expectations was part of the promise he made to his parents, former sharecroppers in rural Georgia, who held the highest hopes for their son, the eighth born of their 12 children.

It all began for Ware with a conversation that took place more than six decades ago, though he remembers it like it was yesterday. He was sitting at the dinner table with his father, who looked across at his son intently before speaking. “We want you to be the first Ware to go to college,” he said.

Ware, then a high school junior, was a bright and ambitious young man. He read everything he could and would claim to anyone who would listen that one day, he’d be a business executive. It was a bold aspiration for a young man who had never even met a Black entrepreneur. But Ware found role models in his parents. His father, Ulas B. Ware, was born in rural Georgia in 1911. Just two generations removed from slavery, he courageously stood up to racism throughout his lifetime.

In 1949, Ulas risked his life to be the first Black man in his county since Reconstruction to vote in Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District. He took the risk, because he recognized that every step forward meant an advancement toward equality. Voting was his step forward; going to college would be his son’s.

The younger Ware took that step eagerly. He earned an undergraduate degree from Clark Atlanta University in 1965 and then a master’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA).

During his studies at Pitt, Ware played a role as a community organizer in inner city neighborhoods developing self-help housing rehabilitation programs. Shortly thereafter while serving as director of housing for the urban league — Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

“After crying my eyes out all day,” says Ware, “I decided I would return to Atlanta to be part of what Dr. King had started. I wanted to help the Civil Rights Movement evolve.”

Ware says his GSPIA education — particularly its emphasis on developing meaningful change in the face of society’s greatest challenges — helped motivate him to pursue political power to chisel away at discriminatory behavior, particularly in the economic system. He successfully ran for Atlanta’s City Council in 1973 and was eventually chosen as its president.

His work caught the attention of leaders at Coca-Cola, which is headquartered in Atlanta. They recruited him in 1974 to be their Urban and Government Affairs specialist. He became a business executive, just as he had aspired to do as a young man.

Throughout his career, he would draw from his father’s courage to stand against inequality. In 1991, following that in-person meeting in London, he instructed each manager to write a plan for developing Black Africans who were capable of running the Coca-Cola business at every level. That’s what they did, Ware says, not just because it was the right thing to do but also because it was good business.

“The notion that empowering local populations is [just about] social change is the wrong notion,” he says. “It’s an economic imperative. There’s a link between doing the right thing socially and making a profit. It is a competitive advantage”.

Ware’s work at Coca-Cola — where, in the 1990s, he was promoted to president of the Coca-Cola Africa Group — connected him with leading figures of South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu and freedom fighter Nelson Mandela. Through Ware’s management, Coca-Cola became an integral part of the movement, building a trailblazing disinvestment and reinvestment strategy that economically and politically empowered Black South Africans. For example, Ware ensured the company offered funding grants to prepare Black South Africans to assume leadership roles at the end of apartheid in 1994, when they would finally be legally allowed to hold such positions.

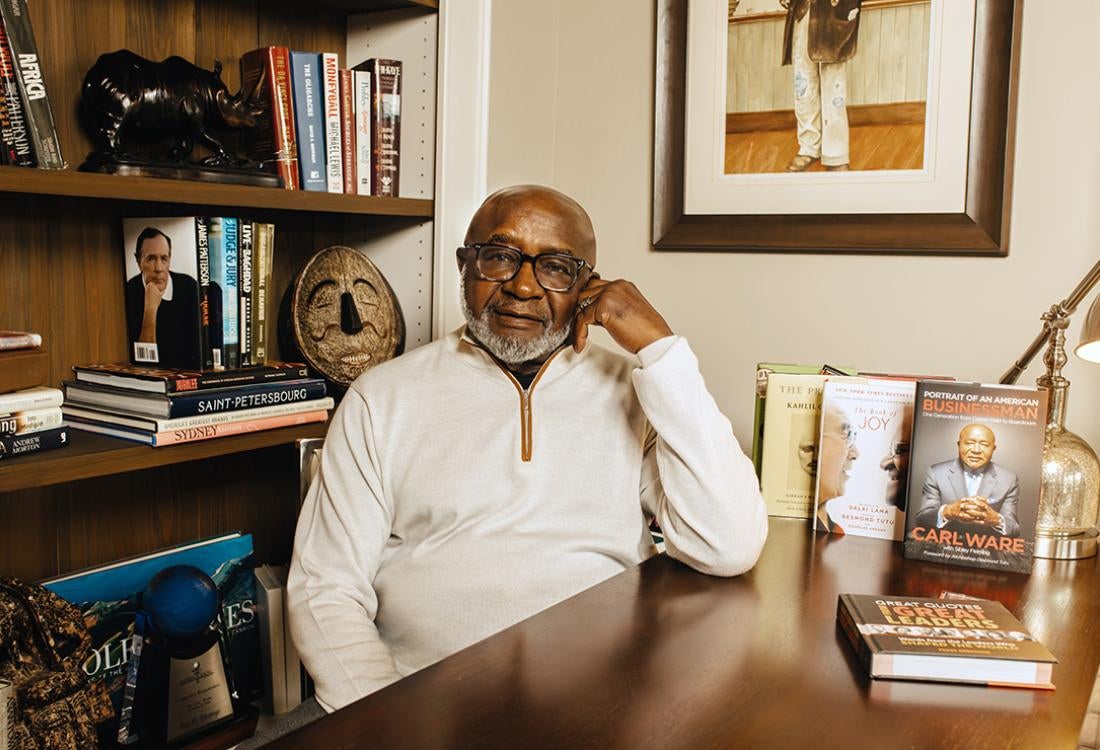

The bonds Ware built were so strong and long-lasting that Archbishop Tutu wrote the introduction to Ware’s autobiography, “Portrait of an American Businessman: One Generation from Cotton Field to Boardroom” (Mercer University Press; 2019). With it, Tutu praises Ware’s values and sense of conscientiousness.

“Carl does not only understand Ubuntu, the Africa philosophy of humaneness,” Tutu wrote, “He lives it and applied it to the corporate, educational, social, political and religious environment in which he played decision-making roles.”

In 2003, the year his father passed away, Ware retired from Coca-Cola as the executive vice president of global public affairs and administration. He now runs Ware Investment Properties from an office in the Georgia home he built after purchasing the 1,000 acres his family once farmed as sharecroppers. (The street’s name: Ulas B. Ware Road.)

Ware hasn’t forgotten his father’s or Pitt’s role in his life. To inspire and support the next generation, he’s created the Carl Ware Fellowship to help others attain a GSPIA education at Pitt. To date, 35 GSPIA students have been chosen as Ware fellows.

“I understand the importance of empowering young scholars through financial support,” says Ware. “I hope the fellowship creates great leaders and great people, whether they’re improving the corporate bottom line or improving the lives of the people they work with. I hope that’s the legacy of the fund — that they’ll go off and change the world.”