Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Finding clues to disease risk could be as simple as a doctor looking inside a patient’s mouth.

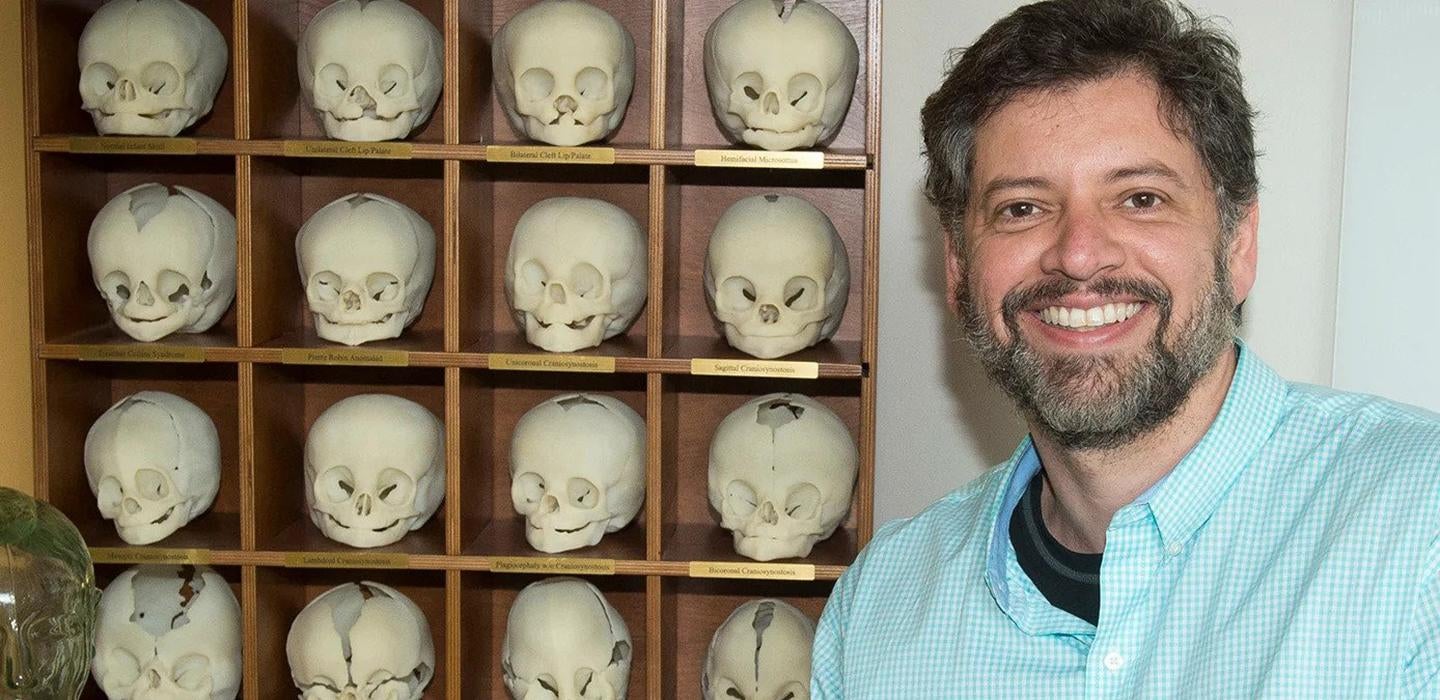

This method is exactly what Alexandre Vieira is studying at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Dental Medicine. His studies suggest that gene mutations influencing how teeth are formed are also consistent with diseases people face later in life, such as kidney disease, asthma and cancer, among others.

“If we can figure out what people’s risks look like with all this genetic dental information, we might be able to tell you to take up a less stressful job or change your diet to avoid these diseases,” said Vieira, the dental school's director of clinical research and of student research. “You can, at some point, personalize the approach that goes from prevention all the way to treatment.”

One example is that individuals with tooth agenesis — the congenital lack of one or more teeth — report more cancer in their families, particularly of the brain, breast and prostate. A 2004 study that Vieira cites found that members of a Finnish family with similar tooth agenesis formations also suffered from colon cancer, with that study's researchers finding a mutational gene called AXIN2 in the family.

“Furthermore, some genes that were independently shown to be associated with cancer are also associated with tooth agenesis,” Vieira said. “One important detail — the tooth agenesis cases included in this study are mostly mild and commonly found in the general population.”

Vieira has multiple studies published suggesting this association, including one in 2014 and another in 2017 that suggested enamel-forming genes may play a part in the decay or crumbling of a tooth, a common chronic disease in children ages 5 to 17 years in the United States.

His studies also suggest that developmental dental anomalies share common genetic contributors to cleft lip and palate.

“We could use a definition of clefts that include the presence or not of dental anomalies to improve our chances to identify gene defects that may explain these conditions, which could improve risk predictions,” Vieira said.

While dental formations can give clues to one's underlying genetics, the only way to conclusively verify whether a person has mutations in these genes is by formal genetic testing, Vieira said. Some common variants could potentially be included in direct-to-consumer panels for DNA testing, often marketed as “verification of ancestry,” some of which may provide a report of individual risks for disease as well.

Vieira is also collaborating with researchers at the University of Utah, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Lausanne in Switzerland and Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania to identify how genetic mutations influence a protein pathway responsible for permanent tooth formation. The project recently received a five-year grant totaling $1.7 million from the National Institutes of Health.

For the next step in his own research, Vieira wants to examine health patterns in individuals over time to see how diseases progress in relation to dental formations, since previous studies have focused mainly on younger people with tooth agenesis.