Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Perspective: On Black fatherhood, gender and family

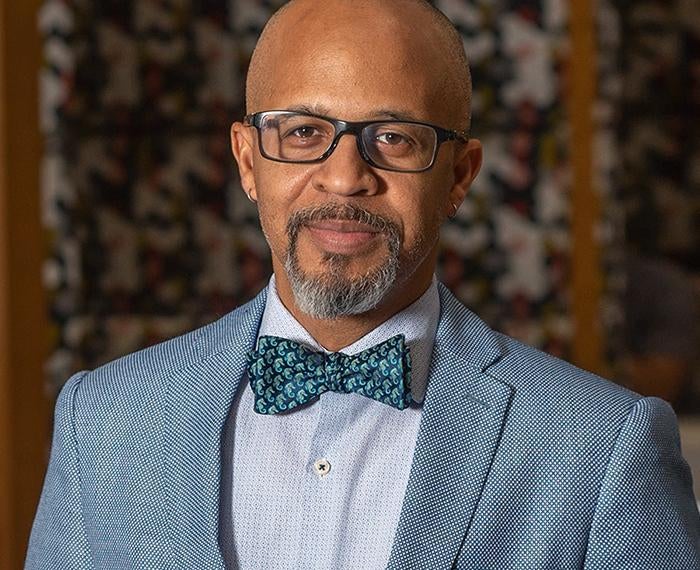

Black fathering: Two words that do not come together easily. As a Black father, I have dealt with regular and open commentary on the deficiencies of Black men. As a scholar trained in anthropology, Black diaspora studies, and Black feminist and Black queer theory, I have spent significant time thinking about what it means to be a Black man who is both a father and husband.

To establish some important background: the Combahee River Collective’s statement of the 1970s laid the groundwork for Black feminist theorizing. In that statement, Black female scholars both critique and stand up for Black men. They state unequivocally their disdain for the pain Black men in their lives caused them, but they also recognize that much of that pain was caused by the dominant power system that told Black men they had to be rich and powerful, and that, to get ahead, Black men must wield that power first and foremost over women. The statement also said that the writers would not abandon their men, nor would they abandon their families.

For Black women, family has been systematically denied throughout history in the diaspora. Slavery, incarceration, welfare states, policing, surveillance, the school-to-prison pipeline and lynching have all been structural and social attacks on the Black family. Having a family was a luxury that was only afforded to the white and to the rich, because watching your children and partners sold or killed in front of you made the idea of family nearly impossible.

However, Black men have received little recognition for their perseverance. Black men have been pathologized as unreliable, oversexualized and immature. Yes, some Black fathers have failed, but the Black fathers who have succeeded are less discussed.

In my Politics of Black Masculinity course at Pitt, I often show a video that has always troubled me of then presidential nominee Barack Obama giving a speech on Father’s Day in 2008 at a Black church. In that speech, he uses the familiar trope that there are too many Black daddies but not enough Black fathers. He over-privileges the nuclear family as the standard, as well as the heterosexual privilege that only men are fathers and they can only be so in a state-recognized marriage. Obama dismisses all of the reasons Black men may be absent from these spaces, and he dismisses all of the Black men who are present for children outside this paradigm. He dismisses my Black queer friend who fathers her partner’s teenage children.

The privatization of prisons and incarceration since the 1980s has made it so that one out of three Black men in America has been or will be incarcerated. The only time I have had a large contingency of Black men in my Politics of Black Masculinity class is when I have taught it in a prison. The men in those classes were carrying on relationships with partners and their children: they were parenting, they were helping with family decision-making, they were arbitrating family disputes — all from distance. Incarcerated Black men have been virtually parenting through letters and phone calls long before COVID-19 forced the rest of us into similar states.

The speech I teach from Obama neglects all of this. Instead, it unfairly places all of the blame and responsibility on Black men who bought into and believe in a world that tells them that men must be violent, men must gain their status through sexual conquest, men must be rich if anyone is to recognize them as men. In a world that regularly denies them equal access to the systems that will allow them elevated status, Black men must seek power out in any way that they can.

In truth, Black masculinity and fathering has long meant raising, caring for and loving children that were not necessarily their biological progeny.

I think of my Uncle Big Junior. He is actually on my wife’s side of the family, long married to my wife’s paternal aunt. He raised and parented all of his wife’s children, none of whom were his biologically — and he parented and raised as his own the white boy his son brought home from school one day whose family neglected him. That boy, now a man, still lives with my wife’s aunt and continues to take care of her long after Uncle Big Junior’s death. He has always called them mom and dad, and no one in their community ever questioned it.

It wasn’t until my wife was 24 and we went to visit her family together for the first time that I asked, “Who is the tall white man in the family photos?” Her simple, matter of fact answer was, “He’s cousin Dale.”

My daughter refers to my closest male friends as uncle. She has Black uncles, Jewish uncles, Muslim uncles, Christian uncles, Polynesian uncles, Asian uncles and white uncles — men whom I trust completely. Some are fathers, some are not. I know they will be there for her if I don’t come home one day. They will step in as her father as I would for their children.

Growing up, I also referred to every one of my dad’s friends as uncles, in addition to my dad’s actual brothers. There was no less respect or responsibility to or from them. They showed care and love to me and my siblings, and we in return showed them respect as if they were our own fathers. They were also sanctioned to discipline us as they would their own children — a seemingly unspoken agreement among these men.

My own father worked tirelessly, as did my mother, to help raise three children. He worked the same unremarkable job of sorting mail for the Canadian postal service most of my life until he retired. He also had his own shortcomings, none of which I could appreciate or fully understand until I became a father.

My daughter and I are the same number of years apart as my father and I. So, as my daughter hit age milestones — 10, 13, 16, 18 — I have reflected on my memories of life at that age, and I wondered what my father was thinking, feeling, wanting, dreaming about at the same times. Did he stress as much as I do when his mother comes to visit, making sure his home and his family were up to her standards? Did he worry about my future? My friends? My happiness?

My father dropped out of school early in order to help support his family, which allowed for his younger brother to focus on school. My uncle eventually earned a PhD and law degree — oh, and he competed in the ’68 Olympics.

This is the father I grew up with.

He allowed me to be a man and a father who is comfortable with women who were smarter and stronger than I am. But none of them are better cooks than me — a trait I got from my father.

Recently, the day after my 50th birthday in late February 2020, I was on my way to the grocery store to get a last-minute item so I could make breakfast for my wife, daughter and mother. On the way, my car swerved slightly. No other cars were around.

I would later find out that a state trooper waited almost two miles before pulling me over. He drove next to me, looked at me, passed me, went in front of me after I made the decision to exit. Then he pulled over to the shoulder and waited for me to pass before turning on his lights and requiring me to pull over.

The officer berated me. All I could get out was, “I didn’t do anything.” Over and over I repeated that statement to the white male officer, my frustration rising. He stepped away, leaving me sitting in my car. When he returned, he said I would receive my fine in the mail. I was dumbfounded. Angry. But I had to remain in control. I had a family to return to; I had to make it home alive. He had a gun, and I did not. He had someone with him, and I did not.

The remainder of my day — driving back home, making breakfast for my family — I was agitated, angry and confused. I replayed my drive to the store over and over in my head. All I could remember was a slight correction when I adjusted the thermostat to make the car warmer. Could that be it? Was that small swerve enough for being pulled over?

I could only conclude: No, but my blackness was. When the officers looked in the car, all they saw was a Black man. Not a father. Not a son. Not a brother. Not an uncle. Not a friend. Not an Ivy League graduate. Not a college professor.

Today, I await my court hearing in July to confront the officer and ask him what he saw that morning. In the meantime, I cannot drive to that grocery store without reliving that experience. It still hurts, months later. It still raises my blood pressure as I pick up bread, flour, milk.

But nothing really happened to me — at least I made it home. George Floyd and so many others before him did not make it home after their encounters. Will I make it home next time?

As we continue to witness the violence done to Black people, I think about my life as a father and husband. George Floyd was a vital part of a family, and now his love is gone. Breonna Taylor was a sister and a daughter, and now her love is gone. This violence snuffs out the love that these people had to give to others. Children will now grow up without their parents’ love.

But others will step in, because that is what Black people have always had to do and will continue to do. Another Black father will step in for George Floyd and fill the void. Another Black mother will step in for Breonna Taylor and make sure that her love is not lost or lacked.

To the Black children who have lost Black men at the hands of white supremacy and policing: we are here to be your fathers, uncles, brothers, teachers or friends whenever you want, and we will love you no less. Our Black heritage demands no less.

Do you have a first-person story to share with the Pitt community? Write to us: pittwire [at] pitt.edu.