Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.A Pitt professor has successfully recreated the first unreleased video game in history.

It’s the latest project from OdysseyNow in the Vibrant Media Lab, run by Zachary Horton, director of the lab and associate professor of English and film and media studies in the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences.

The lab is a cross-disciplinary space filled with vintage video game systems and board games. There, students and faculty work on preserving and playing the systems, among other projects.

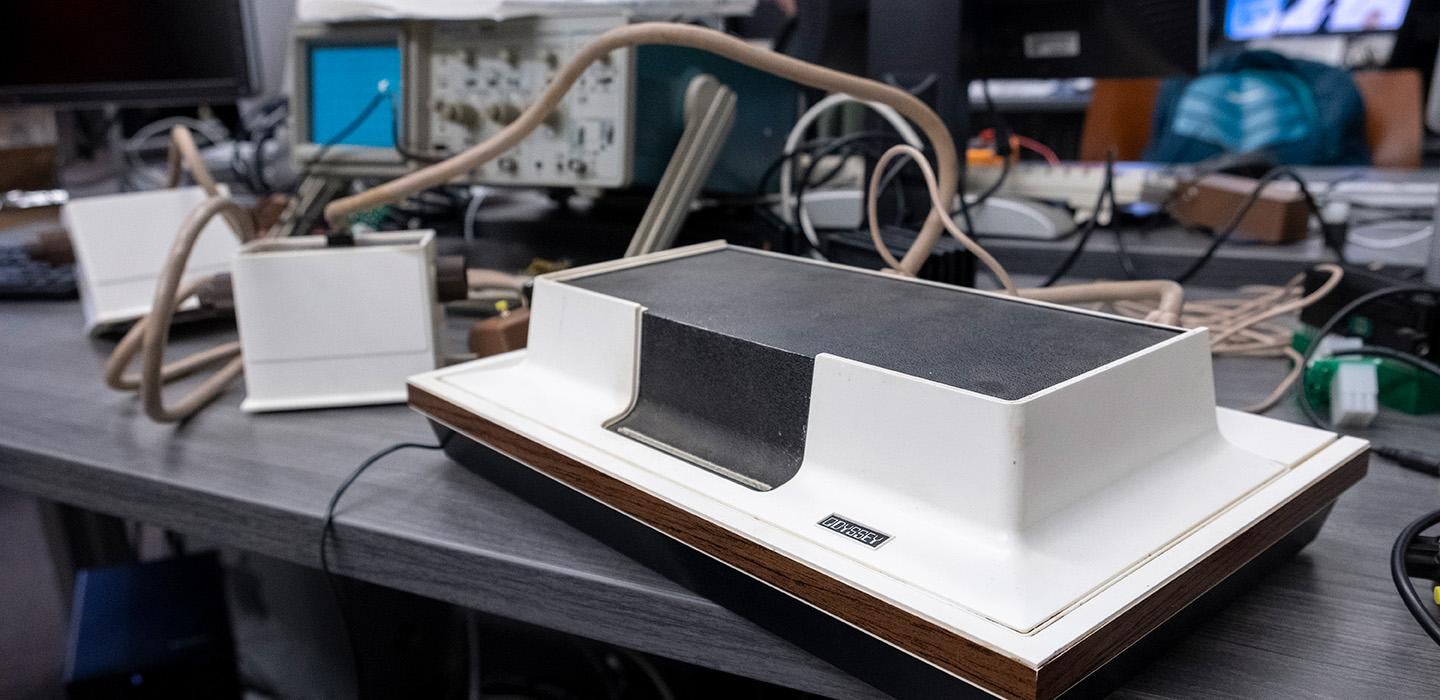

Now in its sixth year, OdysseyNow is the lab’s flagship project that focuses on researching the Magnavox Odyssey, the rare, first-generation home video game console.

“Odyssey gave birth to home video games, the home video game industry, but it also did things that we've lost since then,” he said. “It's not only historically significant to recover a lost game, but it points toward the kind of things that could have been but didn't happen, and maybe that can give inspiration to people today to do things differently.”

[Read more about the OdysseyNow project]

The console is entirely analog and did not have a central processor, which is why the lab’s recreation of the system is such a feat.

Horton has been researching the development of the console and its games for years. The console was originally developed by Ralph Baer, who worked on prototypes throughout the mid-1960s and shopped them around to multiple companies. Each of them rejected the product.

Eventually, though, Magnavox released the Odyssey in 1972, for $100 — about $731 today — which was expensive for the time, Horton noted.

The original system came with 12 games. In 1973, the company hired Don Emery and asked him to make a new pack of games for the Odyssey, which were the last four ever made for the system.

Magnavox also had Emery develop an exclusive game for an unreleased cheaper and less powerful version of the Odyssey: a time trial game called Ski Festival.

However, once the game was fully designed and an advertisement was made, the company scrapped the entire project and Ski Festival along with it. That’s the game that Horton’s team resurrected.

The newfound awareness of the Vibrant Media lab and the OdysseyNow project got the attention of a collector who sent Horton an image of the unpublished, preprint ad.

The ad described the new version of the Odyssey and Ski Festival. It also had an image of the game’s overlay, about 1.5-by-1.5 inches in size, alongside descriptions of the game instructions.

The Odyssey and its games depended on a plastic overlay, which would stick to cathode-ray tube (CRT) television screens because they emitted static electricity. Overlays came in two standardized sizes for 19- and 26-inch screens.

Recreating the game was a complex process. For a year, he, and Jin Jin Wu, a Pitt alum and artist who had worked with Horton on previous Odyssey games, made a series of prototype overlays using what they knew about the console, its history and the other games.

Pitt alumna Stephanie Fletcher, the lab’s playtester for more than three years, joined Horton and Wu after they had developed prototypes of the game. With her input, they recreated a version of Ski Festival that they feel confident was close to Emery’s original vision.

They weren’t sure of the designer’s original intentions behind the movement for the game, so they recreated Ski Festival using two different cards and adjusted the rules depending on which card was used.

Fletcher said when she first grabbed the knobs on the sides of the controller and played on the console, her first comment was, “Oh, it’s like an Etch A Sketch.”

The game also felt more difficult to her than the other Odyssey games. The movement with the inertia system was particularly tough, she said, because making smooth curves with the rotating knobs on the controllers was challenging.

Ski Festival only uses one square on the screen and the player controls that square as they navigate different routes on the overlay.

Horton said it is important to preserve games such as these because it helps inform future media systems.

The relevance of the Odyssey, he said, can be seen in the Nintendo Labo series, which combines the Nintendo Switch console with analogue, cardboard-based peripherals and the company’s renewed emphasis on local multiplayer gaming.

“Understanding the media of the past can help orient us today, not only by tracing a genealogy to help us understand how we got here, but also to uncover the potentials that media systems possessed at one time and later lost,” Horton said. “Thus, the media of the past helps us understand the present while also delivering possibilities for the future.”

— Donovan Harrell, photo courtesy of Vibrant Media Lab

How the games worked

Odyssey games were relatively simple but varied from table tennis, football and hockey to roulette, Simon Says, and Shootout. The console even came with a light gun peripheral, which allowed players to accurately aim and shoot a toy shotgun controller — long before Nintendo’s more popular Duck Hunt.

To keep things simpler and cheaper, the games weren’t programmed with scorekeeping systems or timers. Instead, the games came with packaged cardboard or dial-based timers and scorekeepers.

Rather than a motherboard and pixels, as subsequent gaming systems would use, the Odyssey used digital logic encoded in analog circuitry. The game cards were physically hardwired and encoded with the rules of the games. Once these cards are plugged into the system, they interconnect the different circuits of the Odyssey, creating rectangles on the screen and the rules for how they move and interact.

Almost all Odyssey games were designed to be two player. Solo games weren’t widespread and didn’t come until the end of the 70s, Horton said.

Odyssey games, including Ski Festival, are available to play at the Vibrant Media Lab by appointment via Horton at z.horton [at] pitt.edu.