Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Alumnus Champions Childhood Vaccines

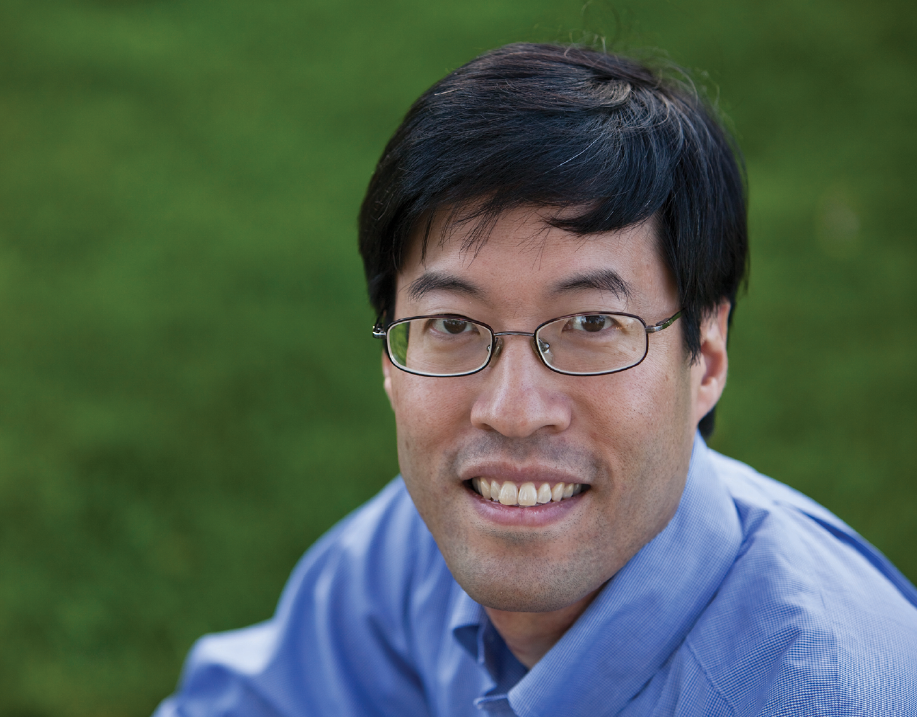

Thanks to widespread childhood vaccination rates, public health experts declared the measles eradicated in North America last year. But the declaration proved to be too soon. Earlier this month, Minnesota saw the largest outbreak of measles in several decades — more than 70 cases since the beginning of 2017. The culprit? Inaccurate scientific information about the vaccine. Alumnus Richard Pan (MED ’91) has seen this before.

Two years ago, TIME called Pan, 51, a hero after he authored Senate Bill 277, which eliminated the personal belief exemption that many parents had used to prevent getting their children vaccinated. The result was a record number of schoolchildren getting the vaccine.

Before becoming a California state senator, Pan, a pediatrician, was on the faculty at the UC Davis Children’s Hospital and helped establish organizations to build healthier communities, one of which resulted in 65,000 Sacramento-area children gaining access to health, vision and dental care.

This spring, Pan returned to Pitt to deliver the commencement address to the School of Medicine’s Class of 2017. “Medicine is a calling,” Pan said. “It's not merely a career.”

Pan recently discussed his work with Pitt Med magazine's Gavin Jenkins:

TIME magazine called you a hero when you authored the vaccination legislation, but tell me how we got here, to the vaccine controversy.

Vaccines are so effective that people have forgotten the diseases they prevent. And so, because people don't have experience with those diseases, it's easy for people to fall prey to people who are creating fear of vaccines through misinformation about dangers of vaccines.

Imagine a set of young parents: “I've never seen measles. None of my friends have ever seen measles. I don't know any kids who've had the measles. So, why do I need to protect my kid against something that no one I know has?” Right?

What happens is that protection gets eroded and that's what we saw here in California. We saw that when we had a pertussis [whooping cough] outbreak in 2010 — 10 infants died, hundreds hospitalized. In 2008 we had a small measles outbreak because an unvaccinated child was in Switzerland, came back with the measles and then infected a bunch of kids in the waiting room in the doctor's office. We still don't know who is case zero, but someone brought measles to Disneyland. But you know what the difference was in 2015? Disneyland is an international destination. People come from all around the world to go to Disneyland. Do you think that's the very first time measles have ever showed up in Disneyland?

Probably not.

Exactly. In previous years, enough Americans were vaccinated so that when someone had measles in Disneyland it didn't go anywhere. It just stopped.

What happened in 2015 would show that we were losing out community immunity. Whoever brought measles to Disneyland got some people infected, and then those people went home and got more people infected because there were enough people unvaccinated to form a chain that allowed it to keep spreading and spreading, and spreading across the state, across the country, even into Canada. (Interesting enough, it didn't really spread into Mexico because enough people were vaccinated in Mexico to keep it from spreading.)

That's the warning sign. It wasn't that measles showed up in Disneyland that was the problem. We lost our community immunity — our ability to contain an outbreak.

Tell me how your legislation came about. Why was it important?

The measles were spreading. Parents from across the state started calling my office and my colleagues saying, "We need to do something about this. I have an infant that is under a year old and she is too young to get vaccinated. What am I supposed to do?"

People started to realize that this was not just like, "Well there are a bunch of people who don't want to get vaccinated, and that doesn't bother the rest of us." So they called and said "Do something about this.”

And so, what SB277 is about — to restore community immunity to neighborhoods in California. It was about keeping children safe at school and keeping our community safe from these diseases.

You returned to Pitt to give your commencement speech this March. What would you say that medical professionals should focus on to prepare for the future?

One of the things I want students to think about as they're graduating — and something I thought about when I was graduating from Pitt — is that we're intensively trained to take care of patients, and we’re learning about what we need to do to help people when they seek our help.

But our mission as physicians isn't just to deliver health care services. The mission of the medical profession is to improve the health — not just deliver health care services — of our patients and our community.

It's not just about what we can do in terms of prescribing things and giving counsel and doing procedures. It's also about stepping out of the hospital, out of the clinic, out of the office and going out into the community and working with people to build healthier environments. To help advocate and lend our expertise to others to help shape our communities in ways that are going to promote health so that everyone can have healthier lives.

A version of this interview originally appeared in the summer issue of Pitt Med magazine. The text here has been edited for clarity and length.